Face to face with our medieval ancestors

Astonishing 3D images and animations of people who died 700 years ago have been created thanks to a collaboration between University of Bradford archaeologists and other specialists.

Their faces were lost to the world but now, thanks to cutting-edge 3D facial reconstruction, it is possible for us to see what three people who died in medieval Scotland actually looked like.

The burials at Whithorn are of huge archaeological importance and the site is known as the “cradle of Scottish Christianity”. The 12th to 14th century Wigtownshire residents, a female, a cleric with a cleft-lip and palate, and a Bishop, were buried at Whithorn Priory in the Dumfries and Galloway region of Scotland.

Using a range of archaeological and forensic science techniques, experts are now reconstructing their past as part of the Cold Case Whithorn project.

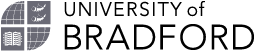

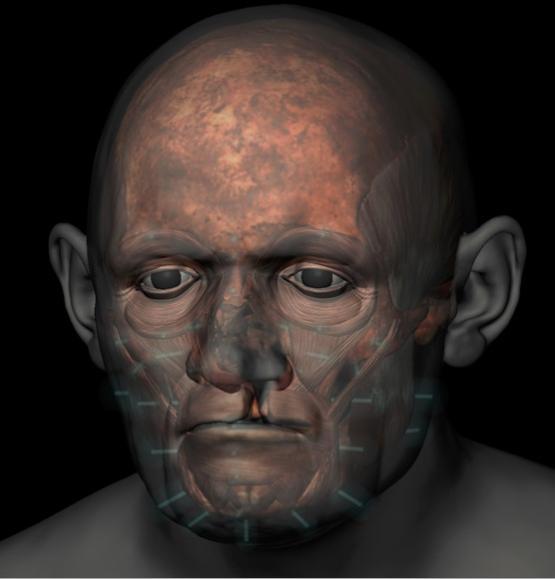

The forensic method of facial approximation, reconstruction and depiction was applied to 3D scans of each skull by craniofacial anthropologist and forensic artist Dr Christopher Rynn.

Dr Rynn said: “This entails the use of facial soft tissue depths, musculature sculpted individually to fit each skull, and scientific methods of the estimation of each facial feature, such as eyes, nose, mouth and ears, from skull morphology.”

National Museums Scotland and Dumfries and Galloway Council museums service loaned the skulls of three medieval people for 3D scanning by Dr Adrian Evans at University of Bradford. They will be unveiled today (Friday September 30), in a joint press conference hosted by the agencies above and the Whithorn Trust.

Dr Shirley Curtis-Summers, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Bradford’s School of Archaeological and Forensic Sciences, has been involved in the Cold Case Whithorn project in collaboration with the Whithorn Trust and project lead, Dr Adrian Maldonado of National Museums Scotland (NMS).

Dr Curtis-Summers led stable isotope analysis on some of the Whithorn burials to understand aspects of diet and mobility and selected the skulls for the 3D facial reconstructions.

She said: “My role as a bioarchaeologist is to examine archaeological skeletons to identify indicators of disease and trauma. I also analysis human bones and teeth for stable isotope analysis, which can inform us about the types of foods people in the past were consuming, and whether they were local to their place of burial.

“I was very excited to be invited by Julia Muir Watt (The Whithorn Trust) and Dr Adrian Maldonado (NMS) to be part of the Cold Case Whithorn team and be involved in the process of choosing the most appropriate skulls for the 3D facial reconstructions.

"This project is of huge significance, because while we can never tell the full story of the lives of these medieval people, being able to reconstruct their diet, mobility, and now their faces, allows us to delve into their past and come face to face with them.”

The Whithorn Trust will unveil the facial reconstructions of these individuals today (Friday September 30) as part of the Wigtown Book Festival, complete with voiceovers created by Urbancroft Films of Glasgow. They will then be displayed at the Whithorn Visitor Centre.

Follow Dr Chris Rynn here: https://www.instagram.com/chris_rynn/?hl=en

Additional information

The University of Bradford has been awarded a coveted Queen's Anniversary Prize for Higher and Further Education for its world-leading work in developing archaeological technology and techniques and its influence on practice, policy and society.

Its experts are world renowned and have been involved in some of the biggest archaeological discoveries and projects in recent times, including the discovery of the Durrington Pits near Stonehenge, and an ambitious £2m search for archaeological remains in the area known as Doggerland, which is now sunken beneath the North Sea.