Archaeology saved my life, says war veteran

“By the time I finish my degree, I will be 69,” muses 67-year-old Sean Cahill, who recently began the penultimate year of a four-year BSc (Hons) Archaeology at the University of Bradford.

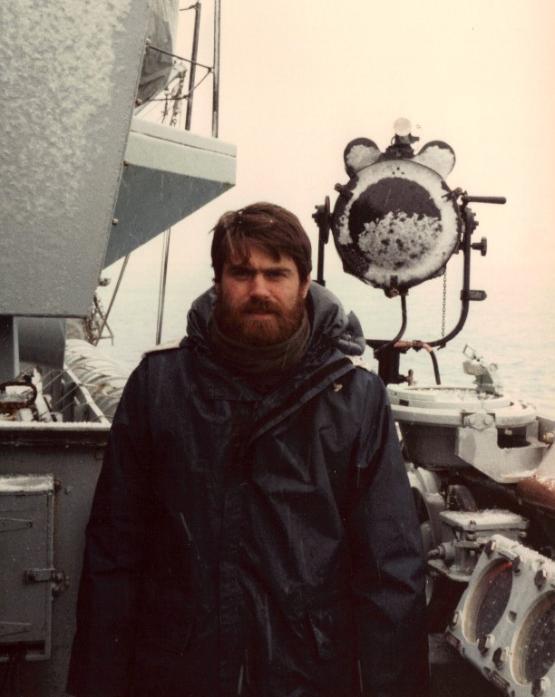

A veteran of the Falklands War, Sean was in HMS Glamorgan in 1982 when it was hit by an exocet missile, killing 13 of his fellow shipmates (another succumbed to his injuries some time later). The trauma of that day, coupled with two subsequent tours of Northern Ireland, would come back to haunt him.

Sean joined the Royal Navy as a boy seaman in 1972 aged just 15. He left as a chief petty officer 24 years later, after which he set up his own commercial diving company, specialising in ‘in shore’ work (anything up to 12 miles out from the coast). It was stressful work that involved underwater construction and demolition, surveying, salvage and even inspecting wrecks carrying live ordinance.

It was partially the stress of that job, coupled with his past experiences, that led to a mental breakdown that changed his life forever.

“The events of the Falklands was something I had never dealt with,” he recounts. “Servicemen and women in the past were always told to ‘shut up or ‘man up’ and that’s the worst thing you can do. There wasn’t really any proper recognition or support. Often, when you have these feelings, you think you’re the only one. It can be very lonely. When I went to the doctors, for example, they just put me on medication. That meant I couldn’t dive. Eventually, I had to leave the business that I spent so much energy setting up, I was also having hallucinations related to my war experiences, and ended up self-medicating, using alcohol to enable me to sleep.”

Around this time, his father was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Sean became his main carer. Despite being one of the lowest moments of his life, it was also the point at which he began to turn a corner.

“Caring for my dad meant I suddenly had responsibility again,” recalls the father-of-three, who also has three grandchildren. “I started to look around for things that veterans could do, and that’s when I found Breaking Ground Heritage.”

Breaking Ground Heritage was conceived in 2015 by an ex-marine who had seen the benefits of using archaeology as a pathway to recovery through the Ministry of Defence’s own programme, Operation Nightingale, which assists the recovery of wounded, injured and sick military personnel and veterans by getting them involved in archaeological investigations.

For Sean, it was a revelation.

"When I dig, I go into my own world. When I was excavating with other veterans, I found that I would mentally retreat into a zone where concentration was key. All other thoughts and memories would recede. I can only compare it to diving; when your helmet leaves the surface, you are in a different zone mentally. Whatever issues you have just go away.

"When I was digging with Operation Nightingale and Breaking Ground Heritage, it was one of the first times I could forget about the war, the memories of the missile attack, and the loss of my shipmates.

“I found I had a real knack for archaeology,” he continues. “I enjoyed it so much I decided to enrol in a degree course. Of course, part of me was saying ‘are you joking?’ - I was in my mid-to-late sixties. By the time I finish my degree, I will be 69, so it’s not like I am going to build a career on the back of this.

"The penny dropped for me when I was on a dig with some other veterans at the Otterburn military training ground in Northumbria. It was a counterintuitive, surreal setting, because there were planes and tactical helicopters flying overhead and practice rounds going off all around us, and in the middle of it all there was this bunch of veterans on an archaeological dig. I suddenly realised, it’s not about getting a job, it’s about the journey.”

Sean has since excelled, earning first class marks in both his first and second year assessments. As part of his degree course, he spent three weeks on a dig in the Orkney Islands, and he has also been on TV talking about his experiences, on shows including Digging for Britain and The Great British Dig.

Later this year, he will embark on a 12-week Mitacs Globalink Research Internship at Thompson River University in Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada to work on a project called First Responders and Military Personnel in Canada and Australia, organised through the University of Bradford. The placement is funded by Mitacs, a non-profit research organisation that works in partnerships with academia, private industry and government to deliver training programs in fields related to industrial and social innovation. Only students with the highest marks are put forward by their university.

The project directly correlates with Sean’s post-degree plans to aid other veterans and will provide an in-depth understanding of the challenges faced by those who work in first responder and military careers and the resources available to those who perform in these public safety functions.

Sean, pictured above during his days as a commercial diver, adds: “For someone who left school at 15 with no qualifications, this is something I never expected. I have a passion for archaeology I didn’t know I had. Part of me wishes this had happened 30 years ago but it’s happened now, so you just have to crack on.

“You could say this is a prime example of a late flourisher - god knows what my school teachers would have made of it.

“If I could give advice to anyone suffering from PTSD, I would say just go talk to someone, anybody, don’t keep it to yourself. There is help and support out there. Archaeology saved my life. It pulled me back from the brink.

"My hope is that I will eventually work as a full-time member of staff or volunteer at Operation Nightingale, mentoring other veterans through archaeological investigations.

"In this later stage of life, I have finally found my calling. I now have a mission, which is to help other veterans through archaeology.”