Geo-archaeologists hunting for evidence of humans amid sunken ice age landscapes

Geo-archaeologist Dr Simon Fitch from the University of Bradford is about to embark on a “first of its kind” mission to map sunken ice age landscapes lost to the oceans millennia ago.

On March 30, Dr Fitch will travel to Split, Croatia to begin a five-day long survey of the Adriatic seabed using state-of-the-art underwater 3D seismic sensors.

It is the first in a series of expeditions over the next five years that will map parts of the Adriatic and North Sea, as they were between 10,000 and 24,000 years ago, when sea levels were around 100m lower than they are today.

Above: Dr Simon Fitch from the University of Bradford.

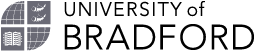

The Life on the Edge project is part of a UKRI future leaders fellowship for Dr Fitch, which last year attracted just over £1m in funding from UKRI, as well as £400,000 in-kind ship time from VLIZ (Flanders Marine Institute), and a PhD studentship from the University. Partner institutions include the University of St Andrews, Scotland and University of Zagreb, Croatia.

The University of Bradford's Faculty of Life Sciences now has the largest submerged landscapes research group in the world and is one of the few places specialising in what is an emerging academic discipline.

Future Leadership Fellow Dr Fitch said: “This is the first time anyone is going more than 500m from the coastline in the Adriatic to map the seabed. We know humans once lived on the land down there because trawlers regularly dredge up artefacts. This is about finding out who we are as a species and where we come from.

“We have an incomplete picture of human history. If we go back in time to the period known as the late Paleolithic - so, between 10,000 and 24,000 years ago - that is when we had the last ‘glacial maximum’. It’s when the ice age was at its peak. Sea levels were up to 100m lower than they are today. They would have been like that for thousands of years. It means a lot more land was exposed and people would have lived there.

“We know most human populations like to live on the coastline, so it’s likely there were settlements on what is now the seabed. Our aim is to find evidence of those settlements and then recover the archaeology. “

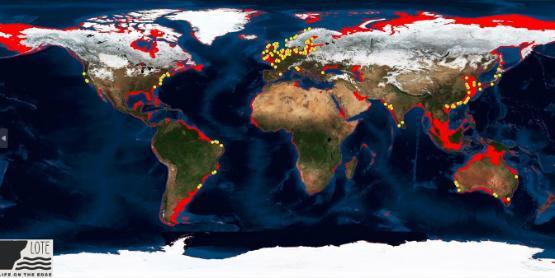

Above: 3D rendering of the Adriatic off Croatia, with red line showing coastline as circa 22,000 years ago.

The Life on the Edge expedition will take in sites both in the Adriatic and North Sea. Archaeologists from Bradford, along with collaborators from the University of Split and Flanders Marine institute (VLIZ), are working with commercial companies, who are already mapping seabeds as they prepare to install wind farms.

State-of-the-art supercomputers installed at the University of Bradford are being used to crunch reams of data and turn it into readable maps, showing lost landscapes, including where rivers ran, hills and other features.

Dr Fitch, who will travel to Croatia to conduct underwater mapping with the University of Split later this month, said: “The technology we use produces masses of data. To process that, we need super powerful computers. Whereas most people will be used to a laptop having something like a 256GB hard drive and 8GB of RAM, one of the computers we use at the university has 256GB of RAM, and a storage capacity running to hundreds of terabytes.”

Above: Workers on a research vessel.

The Life on the Edge project has already attracted attention from overseas, with Dr Jessica Cook Hale travelling from the University of Georgia to join the project. A seasoned archaeologist of more than 20 years, she has already dived prehistoric underwater sites off both the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coastlines.

She said: “Bradford is one of the few places doing this. I looked at this project from afar and wanted to be a part of it, so I’m thrilled to be joining the team. Carrying out geo-archaeology on submerged landscapes is really the only way to approach the problem of finding out about our prehistoric ancestors. As archaeologists, we’re naturally curious, we always want to ask ‘what came before?’

“When we look for evidence of humans in prehistory, one of the best places is often the midden-heaps - or rubbish dumps - because that contains a concentration of artefacts. We know from experience human populations like to live along the coast, so once we get an understanding of the topography, we can then make an educated guess as to where they might have lived at a time when sea levels were much lower than they are today.”

Above: picture of Dr Jessica Cook Hale diving off the coast of Florida as part of a different project.

Part of the brief for the Life on the Edge project is to recruit and train new geo-archaeologists.

Dr Fitch, who will travel to Croatia to conduct underwater mapping later this month, added: “It really is exciting, because not only are we undertaking explorations that have never been done before, we’re also going to be training a new generation of geoarchaeologists.

“It’s aptly called the ‘Life on the Edge’ project. We are at the edge of technology, of archaeological research, and the edge of human existence, in terms of where people used to live. We’re doing things no-one has done before and going places no-one has been, so whatever we find really will be a world first."